Today’s news of a looming showdown between the FTC and the Commerce Department over privacy appears to involve an important question: Will there be a “Do Not Track” option for consumers when it comes to behavioral targeting?

Today’s news of a looming showdown between the FTC and the Commerce Department over privacy appears to involve an important question: Will there be a “Do Not Track” option for consumers when it comes to behavioral targeting?

Here’s my take on three possible ways Do Not Track might be implemented:

1. Browser-based blocking

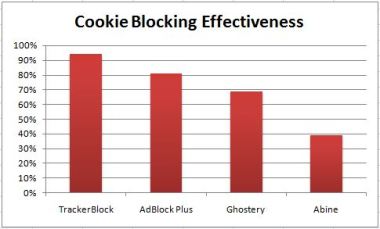

It’s not difficult to engineer browsers to implement functionality like TrackerBlock, which literally stops selected data companies from accessing cookies on your computer (and deletes other identifiers they may leave behind). For the consumer, this kind of “Do Not Track” is even more effective than “Do Not Call.” Marketers aren’t just prohibited from calling, you can actually make them forget your number.

How would this be different from just turning off third-party cookies, as you already can in your browser controls? Turning off all cookies is a blunderbuss — lots of cookies are beneficial and not used for behavioral tracking, so that turning them all off degrades the rest of your browsing. By identifying which domains and cookies are used for tracking (something companies would need to certify), the browser can differentiate between tracking cookies and non-tracking cookies. In TrackerBlock the user can select individual companies to block, or with one click can block all companies or just those without best practices and oversight. (Take a look at the TrackerBlock control panel to see what I mean.)

This might be the most effective way to implement “Do Not Track,” but it’s not obvious that the FTC’s mandate stretches to browser design, which is one step removed from ad targeting practices. But the FTC does have sway over the ad targeters themselves, who could be required to offer Do Not Track browser add-ons as part of the notice-and-choice experience.

Is this approach to Do Not Track really practical, given that most users won’t install an add-on? Based on my own experience, installing a browser add-on for Do Not Track actually takes less time than registering your phone number for Do Not Call. Many users still fear any sort of software installation, but this will remain a barrier unless and until Do Not Track becomes embedded in native browser controls.

2. Opt-out cookies

The current framework of opt-out cookies might be seen as a form of “Do Not Track,” in that it allows a consumer to signal their privacy preference to each company through an opt-out cookie. These can be offered in aggregate, and industry groups and volunteers even offer browser add-ons that make opt-out cookies permanent.

Unfortunately, today’s opt-out cookies serve only to indicate the consumer’s preference not to have ads targeted based on their behavior; opt-out cookies do not promise to prevent the continued collection of behavioral data. Ad delivery companies may still retain a tracking cookie on your computer separate from the opt-out cookie, which continues to transmit behavioral information. If the goal of Do Not Track is consumer choice over data collection, the current form of opt-out cookies don’t really cut it.

There have also been proposals for a universal header, which, like an opt-out cookie, would automatically transmit the opt-out preference as part of every interaction with any server, including ad servers. By ditching the need for individual opt-out cookies, this is easier to maintain as the use of targeting spreads to more companies and brands; but standing alone it doesn’t provide any more assurance about data collection because tracking cookies may still be in use.

3. Data collection opt-outs

A hybrid approach could focus on improving the current opt-out functionality to make it more effective as a Do Not Track method. Here’s how it could work:

- When a consumer requests an opt-out cookie, the non-unique cookie is written over each and every cookie that the company uses to store behavioral information.

- Tracking companies publicly certify which domains and cookies are used for behavioral information. Industry organizations or private auditing firms can query and spot check companies on the back end to make sure certification is accurate.

- Using test machines in the wild, verification vendors and watchdogs can easily test to confirm that generic opt-out cookies are written on request and are not altered over time.

- The enhanced notice-and-choice experience would enable users to get a full set of improved opt-out cookies from all networks in a few clicks. Users who clear cookies regularly would have an option to install bookmarklets or add-ons to store opt-out preferences and replace them more easily.

Here’s the operational catch: companies that currently store behavioral and non-behavioral data in the same cookie must segregate those uses. But in a Do-Not-Track world, segregating behavioral and non-behavioral cookie functions is simply good practice, like separating accounting functions where there’s a potential conflict of interest. Otherwise you’re shifting the burden of trust completely the consumer.

Which approach is best?

Since the current opt-out framework doesn’t really provide a “Do Not Track” option, the choice might come down to Door Number 1 (browser-based blocking) and Door Number 3 (an improved opt-out framework that actually controls data collection).

From a consumer point of view, browser-based blocking may be the most verifiable. From an industry point of view, data-collection opt-outs may preserve the most operational flexibility, by permitting non-behavioral tracking to continue. The good news is that both approaches can and would co-exist, so that consumers don’t need to make any compromise.

Here’s the crucial point: In either case, tracking companies must identify the domains and cookies they use for tracking, those must be isolated from non-behavioral cookies, and those distinctions must be subject to back-end compliance reviews. Only once that is in place does Do Not Track become a practical possibility.

By the way, no Do Not Track system can deal with all rogue tracking methods, like Flash cookies, browser fingerprinting or IP-address tracking. Think of that like the occasional telemarketer who still calls you at dinnertime in defiance of No Call List. It’s inevitable and regrettable, but doesn’t undermine the fundamental value of the program.

A spooky experience with drug-ad targeting was the initial inspiration for the PrivacyChoice project, so it won’t surprise you that I support the call for an FTC investigation into pharmaceutical ad targeting. There’s a big difference between building a profile about what kind of car you want to buy and a profile that infers that you’ve just been diagnosed with cancer. Ask consumers and they would overwhelmingly say that this kind of targeting should be opt-in, not opt-out.

A spooky experience with drug-ad targeting was the initial inspiration for the PrivacyChoice project, so it won’t surprise you that I support the call for an FTC investigation into pharmaceutical ad targeting. There’s a big difference between building a profile about what kind of car you want to buy and a profile that infers that you’ve just been diagnosed with cancer. Ask consumers and they would overwhelmingly say that this kind of targeting should be opt-in, not opt-out.